I. The Unseen Threat in Your Update Server: A "Keys to the Kingdom" Vulnerability

Within the complex architecture of enterprise security, the Windows Server Update Service (WSUS) stands as a ubiquitous and fundamentally trusted component. It is the silent workhorse operating in the background, the central nervous system for patch management, ensuring that thousands of endpoints receive the critical security updates necessary to maintain cyber hygiene and defend against an ever-evolving threat landscape. Organisations across Australia and the globe depend on its reliable function to close vulnerabilities and fortify their digital estates. This report, however, addresses a critical and alarming scenario: what happens when this trusted defender becomes the ultimate insider threat?

The emergence of CVE-2025-59287 represents not merely another software flaw, but a fundamental breach of the trust relationship between an organisation's security posture and its core management tools. An adversary who gains control over a WSUS server does not just compromise a single machine; they seize the "keys to the kingdom." They command the very mechanism responsible for distributing security and integrity across the network. This privileged position allows an attacker to turn the entire update infrastructure into a weapon, capable of deploying malicious code disguised as legitimate patches to any and every connected system. The psychological impact of such a compromise on security teams is profound. It weaponizes a tool they rely upon for defence, forcing them into a state where their own infrastructure must be treated with suspicion. This erosion of trust complicates every facet of incident response and recovery, handing a significant advantage to the adversary before the battle has even begun.

The threat posed by CVE-2025-59287—a critical, remotely exploitable, unauthenticated vulnerability now being actively used by attackers—is therefore not a problem to be delegated solely to system administrators. Its potential for catastrophic business disruption, from widespread ransomware deployment to silent espionage, elevates it to a strategic risk that demands the immediate attention of technical and business leadership. This analysis will deconstruct the vulnerability, trace its alarming evolution from a flawed patch to a weaponized exploit, and argue that for Australian organisations, the only path to true resilience lies beyond reactive patching and in the realm of proactive, adversary-emulation-based security validation.

II. Deconstructing CVE-2025-59287: The Anatomy of a Critical Flaw

To fully grasp the severity of CVE-2025-59287, it is essential to understand both the role of WSUS in a typical enterprise environment and the precise technical mechanics of the vulnerability itself.

WSUS Architecture in the Enterprise

WSUS operates on a hierarchical model. A central "Upstream Server" connects to Microsoft's update servers over the internet to download patches. Internal "Downstream Servers" then connect to this upstream server to receive and distribute those patches to client workstations and servers within the local network. This architecture is designed for efficiency and control, but it creates a powerful central point of distribution. A compromise of the upstream server can have a cascading effect, potentially compromising every downstream server and, by extension, every client they manage. This structure makes WSUS an incredibly attractive target for adversaries seeking to bypass network segmentation and achieve widespread lateral movement.

Technical Deep Dive

The vulnerability is rooted in a classic but severe software security flaw known as "Deserialization of Untrusted Data," catalogued as CWE-502. The attack unfolds through a precise sequence of events targeting the WSUS reporting web services:

The Attack Vector: A remote, unauthenticated attacker sends a specially crafted network request to the WSUS server. This request targets the

GetCookie()endpoint and contains a maliciousAuthorizationCookieobject.The Mechanism: The WSUS server receives this malicious cookie. It proceeds to decrypt the cookie's data using an AES-128-CBC cipher and then deserializes the resulting object using the

BinaryFormattermethod. The critical failure occurs here: the server performs this deserialization without properly validating that the resulting data is safe or of an expected type.The Result: By providing a malicious object, the attacker tricks the server into executing arbitrary code in the context of the WSUS service, which typically runs with high-level SYSTEM privileges.

This exploit is particularly egregious because Microsoft itself has long deprecated the use of BinaryFormatter, explicitly warning developers that the method is inherently unsafe when used with untrusted input due to its inability to prevent this exact type of attack. Its continued presence in a critical, internet-facing component represents a significant and exploitable engineering oversight.

Quantifying the Risk

The technical details translate into a risk profile that represents a worst-case scenario for a network-based vulnerability. The Common Vulnerability Scoring System (CVSS) provides a clear, data-driven assessment of its severity.

CVE-2025-59287

The CVSS vector string is particularly telling for technical leaders:

Attack Vector: Network (AV:N): The vulnerability can be exploited remotely over a network.

Attack Complexity: Low (AC:L): It requires no special conditions or complex techniques to exploit.

Privileges Required: None (PR:N): The attacker does not need any credentials or prior access.

User Interaction: None (UI:N): The attack requires no action from a user, such as clicking a link or opening a file.

Impact: High (C:H, I:H, A:H): Successful exploitation leads to a complete loss of Confidentiality, Integrity, and Availability of the targeted WSUS server.

This combination confirms that CVE-2025-59287 is a remotely executable, unauthenticated, and trivial-to-exploit vulnerability that results in a full system compromise.

III. A Timeline of Crisis: From Flawed Patch to Active Exploitation

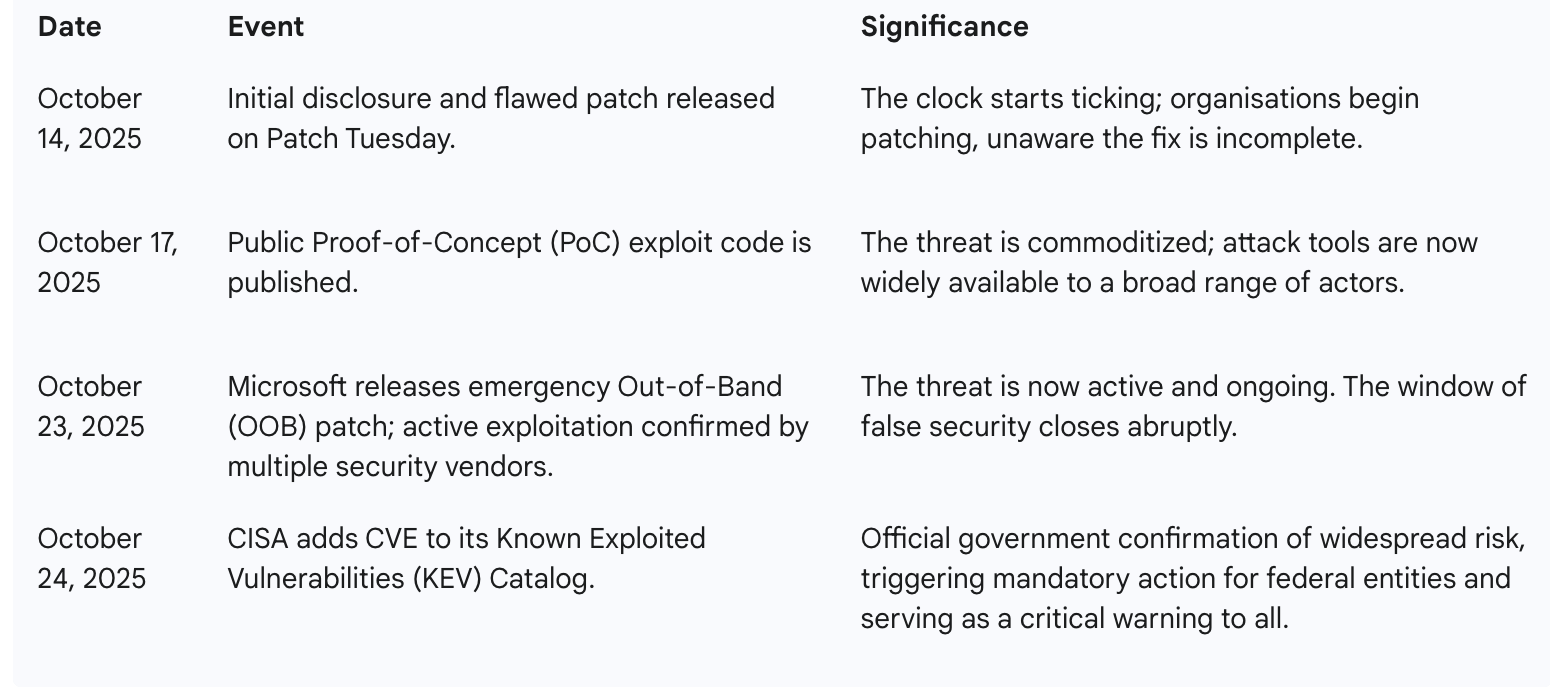

The story of CVE-2025-59287 is not just one of a critical vulnerability, but also a case study in the dangers of a flawed patching process and the rapid pace at which modern threats evolve. The timeline of events created a critical window of exposure, leaving even diligent organisations vulnerable.

CVE-2025-59287 timeline

Official government confirmation of widespread risk, triggering mandatory action for federal entities and serving as a critical warning to all.

This sequence of events powerfully illustrates the "patching paradox" and the inherent weakness of a purely compliance-centric security model. An organisation that prides itself on its key performance indicators for patch deployment—for instance, applying all critical patches within a 14-day window—would have acted promptly after the October 14th Patch Tuesday. They would have deployed the initial update, and their vulnerability scanners and compliance reports would have marked CVE-2025-59287 as "remediated."

However, because that initial patch was incomplete, this state of compliance was a dangerous illusion. The organisation was, in fact, still completely vulnerable. The period between October 14 and the release of the emergency patch on October 23 was a window of false security. During this time, the publication of a PoC exploit on October 17 dramatically lowered the technical barrier for attackers.8 When active exploitation began on October 23, these "compliant" organisations were just as exposed as those who had not patched at all.

This real-world failure demonstrates that security cannot be measured by checklists or the speed of patch deployment alone. True security is not a theoretical state of compliance but an empirically validated state of resilience. It proves that mitigating controls must be tested to confirm they are actually effective, not just present. Without this validation, organisations are operating on faith—a faith that, in this case, was misplaced, leaving them exposed to a critical, actively exploited threat.

IV. The Attacker's Playbook: How CVE-2025-59287 is Being Weaponised

The theoretical risk of CVE-2025-59287 rapidly became a practical reality. Security researchers observed attackers exploiting the vulnerability in the wild, providing a clear view of their initial tactics and objectives.

In-the-Wild Exploitation

Initial reports from security firms like Huntress described the attacks as simple "point-and-shoot" techniques, underscoring the low complexity of the exploit following the release of the PoC. The observed post-exploitation activity focused on immediate reconnaissance. Attackers, having gained SYSTEM-level access on the WSUS server, were seen spawning Command Prompt and PowerShell processes directly from the IIS worker process (w3wp.exe) or the WSUS service binary (wsusservice.exe).

They executed basic commands to map the compromised environment, such as net user /domain to enumerate all user accounts in the Active Directory domain, and ipconfig /all to gather detailed network configuration data.1 The output of these commands was then exfiltrated to an attacker-controlled remote server.1 This behaviour is a clear indicator that attackers are using the initial WSUS compromise as a beachhead to understand the network's structure, identify high-value targets, and plan their next move.

The Red Team Perspective: Simulating the Full Attack Chain

While the observed attacks focused on reconnaissance, a sophisticated adversary—or a red team emulating one—would leverage the unique position of a compromised WSUS server to execute a far more devastating attack chain. The strategic goal is not just to compromise the WSUS server itself, but to use it as a master key to unlock the entire network. This is accomplished by abusing the core functionality of WSUS for lateral movement, a technique well-documented by offensive security researchers and encapsulated in tools like SharpWSUS.

The full attack chain would proceed as follows:

Initial Compromise: The attacker gains their initial foothold by exploiting CVE-2025-59287, achieving remote code execution with SYSTEM privileges on the primary WSUS server.

Internal Reconnaissance and Target Identification: From the compromised server, the attacker enumerates all computers managed by WSUS. This provides a comprehensive list of potential targets across the network, including domain controllers, database servers, and critical application hosts.

Target Isolation: To avoid detection and collateral damage, the attacker creates a new, innocuous-sounding update group on the WSUS server (e.g., "Critical Server Patching Pilot"). They then move their high-value target, such as a domain controller, into this isolated group.3

Malicious Update Creation: The attacker crafts a malicious "update" package. A key constraint of this technique is that the payload must be a legitimate, Microsoft-signed binary to avoid suspicion. However, this is a low hurdle, as numerous signed binaries can be used for malicious purposes (a technique known as Living-off-the-Land). The attacker can use a tool like

PsExec.exeorMsiExec.exeto execute a secondary payload, such as a command to create a new administrative user or deploy ransomware.Deployment and Execution: The attacker approves this malicious update for deployment only to the isolated group containing the high-value target. They then simply wait for the target machine's scheduled check-in time. When the domain controller connects to WSUS to request updates, it will download and execute the malicious package, believing it to be a legitimate patch from a trusted internal source.

The strategic impact of this attack path cannot be overstated. Modern network security is built on the principle of segmentation—separating critical assets into protected zones to contain breaches. However, WSUS, by its very nature, is designed to traverse these segments. Firewall rules are almost always configured to allow clients from all network zones to communicate with the central WSUS server on ports 8530 and 8531. An attacker who controls the WSUS server inherits this privileged network position. They can use the trusted WSUS protocol as a covert channel to push malicious code into otherwise inaccessible, highly secured network segments, rendering years of segmentation efforts completely useless. The WSUS server becomes a network chokepoint, where a single point of failure leads to the systemic compromise of the entire enterprise.

V. The Australian Imperative: Placing the WSUS Threat in Local Context

While CVE-2025-59287 is a global threat, its implications are particularly acute within the Australian cybersecurity landscape, which is characterized by increasing attacks and a stringent regulatory environment for critical infrastructure.

Connecting to the National Threat Landscape

The Australian Signals Directorate's (ASD) Australian Cyber Security Centre (ACSC) Annual Cyber Threat Report 2024-25 paints a stark picture of the environment in which Australian organisations operate. The report highlights a staggering 83% increase in notifications of potentially malicious cyber activity issued by the ACSC. It underscores the persistent and growing threat from both state-sponsored actors and sophisticated cybercriminals who are relentlessly targeting Australian governments, businesses, and critical infrastructure.13

Crucially, the report identifies "compromised assets, networks, or infrastructure" as the most frequently reported type of cybersecurity incident, accounting for 55% of incidents affecting critical infrastructure. The exploitation of CVE-2025-59287 aligns perfectly with this trend, providing adversaries with a direct and highly effective method for achieving widespread network compromise. The ability to gain control of a central management tool like WSUS is precisely the kind of high-impact capability that these threat actors seek.

Implications for Critical Infrastructure (SOCI Act)

For the growing number of Australian organisations governed by the Security of Critical Infrastructure (SOCI) Act 2018, this vulnerability poses a direct and significant challenge to their compliance and operational resilience obligations. The SOCI Act mandates that responsible entities establish and maintain a risk management program (RMP) that identifies and mitigates hazards, including cyber threats and supply chain vulnerabilities.

A vulnerability in a foundational software distribution platform like WSUS must be viewed as a critical software supply chain risk. An attacker who compromises WSUS can disrupt the integrity of the entire software update process, which is a cornerstone of cyber defence. For operators of essential services—in sectors like energy, healthcare, communications, and finance—a compromised WSUS server could be used to deploy disruptive malware, leading to significant operational downtime, service outages, and a clear failure to meet SOCI Act obligations. For entities responsible for Systems of National Significance (SoNS), the threat is even more severe. An adversary could use a compromised WSUS server to gain persistent access to the nation's most vital assets, directly threatening Australia's economic stability and national security.

This context transforms the WSUS vulnerability from a mere technical issue into a potential tool for "grey zone" warfare. The ACSC has explicitly warned that state-sponsored actors are actively working to position themselves for potential disruptive attacks at times of strategic advantage. A compromised WSUS server is the perfect vector for such an operation. An adversary could use it to deploy a dormant payload—such as a logic bomb, a wiper, or a persistent backdoor—disguised as a routine update. This malicious capability could be pre-positioned across an entire critical infrastructure network, remaining latent and undetected until activated. This scenario moves beyond data theft and cybercrime into the realm of national resilience and sovereignty, aligning directly with the most serious threats identified by the ASD.

VI. Your Strategic Response: Moving from Reactive Patching to Proactive Defence

A threat of this magnitude requires a response that is layered, disciplined, and extends beyond immediate remediation. A comprehensive strategy must move from tactical triage to proactive validation and, ultimately, to the strategic resilience that can only be achieved through adversarial emulation.

Layer 1: Immediate Tactical Mitigation (The "Stop the Bleeding" Phase)

This phase is about immediate, decisive action to contain the threat, based on the official guidance from Microsoft and CISA. These steps are non-negotiable and must be treated with the highest priority.

Action 1: Patch Immediately. Apply the correct out-of-band (OOB) security update to all affected Windows Server versions. The relevant updates include KB5070881, KB5070882, KB5070883, KB5070884, and others corresponding to specific server versions. This OOB update supersedes the flawed patch from the October 14th Patch Tuesday.

Action 2: Reboot. A system reboot is required after the patch is installed to ensure the mitigation is fully applied and the system is protected.

Action 3: Use Workarounds if Patching is Delayed. In situations where immediate patching is not feasible due to operational constraints, Microsoft has provided temporary workarounds. These include completely disabling the WSUS Server Role on the affected server or, more surgically, blocking all inbound traffic to TCP ports 8530 and 8531 at the host firewall.1 It is critical to understand that these actions will render the WSUS server non-operational, preventing clients from receiving any updates.

Layer 2: Proactive Security Validation (The "Confirm and Harden" Phase)

Completing the tactical mitigation is only the first step. The "patch and pray" approach is insufficient given the active exploitation of this vulnerability. Technical leaders must challenge their teams with the critical follow-up question: "How do we know we are truly safe?"

Action 4: Hunt for Compromise. Operate under the assumption of a breach. Security teams must proactively hunt for Indicators of Compromise (IOCs) related to the observed in-the-wild attacks. This includes searching logs for suspicious PowerShell or Command Prompt execution originating from the

w3wp.exeorwsusservice.exeprocesses, and analyzing network traffic for unusual outbound connections from WSUS servers to unknown domains.1Action 5: Validate Patch Deployment and Configuration. Use vulnerability management and asset inventory systems to confirm that the correct OOB patch has been successfully deployed across the entire fleet of WSUS servers. This is also the time to conduct a thorough configuration review of all WSUS servers, ensuring that management access is restricted to trusted administrative networks and that host firewall rules are hardened to minimize the attack surface.

Layer 3: Adversary Emulation (The "Build True Resilience" Phase)

This is the most critical phase for achieving long-term, verifiable security. The only way to be certain that defences can withstand a sophisticated, multi-stage attack leveraging a compromised WSUS server is to simulate that exact attack in a controlled, objective-driven manner.

Action 6: Commission a Red Team Engagement. A specialized red team engagement provides empirical evidence of an organisation's security posture against this real-world threat.19 Such an exercise would not stop at a simple vulnerability scan. It would simulate the adversary's complete playbook, including:

Attempting to validate the patch's effectiveness against the known exploit for CVE-2025-59287.

Executing the post-exploitation tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs), specifically emulating the abuse of WSUS for lateral movement as described in the SharpWSUS methodology.

Testing the Security Operations Centre's (SOC) and blue team's ability to detect and respond to the specific artifacts of this attack, such as the creation of suspicious update groups, the deployment of non-standard update packages, or the presence of unexpected signed binaries in the WSUS content directory.

This process moves security from a theoretical state based on compliance to an empirically tested reality. It provides leadership with genuine, evidence-based confidence in their organisation's resilience against the threats they are most likely to face.

Adversary Emulation phases

VII. Executive Briefing: Key Actions for Australian Business Leaders

The critical vulnerability in the Windows Server Update Service, CVE-2025-59287, represents a clear and present danger to Australian organisations. This is not a routine security flaw; it is a strategic risk that weaponizes a core IT management asset, turning a trusted defender into a potential single point of catastrophic failure. Active exploitation in the wild, combined with a CVSS score of 9.8, necessitates an urgent and comprehensive response that goes beyond standard patching protocols. For business and technical leaders, the following actions are imperative.

Acknowledge the Severity: Recognise that CVE-2025-59287 is a critical, actively exploited threat that fundamentally undermines the trust in your core IT infrastructure. Direct your teams to treat this with the highest level of urgency.

Mandate Immediate and Correct Patching: Instruct your technical teams to apply Microsoft's specific emergency out-of-band patch for CVE-2025-59287 across all WSUS instances without delay. Ensure they understand that the initial October 14th patch was insufficient and must be superseded.

Question Your Assumptions: Move beyond a compliance mindset. The critical question is not simply "Did we patch?" but "How have we validated that the patch is effective and that no prior compromise occurred?" Demand evidence of proactive threat hunting and configuration validation.

Invest in Adversarial Validation: The weaponization of trusted infrastructure is a hallmark of sophisticated attacks. The only way to truly know if your defences, detection capabilities, and response procedures can withstand this attack is to test them. Commission an independent penetration test or red team engagement focused specifically on simulating this attack chain to gain empirical evidence of your organisation's security posture.

Review Your SOCI Act Obligations: If your organisation is a critical infrastructure operator under the SOCI Act, this vulnerability has direct implications for your mandated risk management program. Engage with your compliance and security teams to review how this software supply chain threat impacts your operational resilience and ensure your mitigation strategies are sufficient to meet your legal and regulatory obligations.